Issue 10 – Will Washington State Finally Tax the Rich to Fund Public Schools?

Will 2026 be the year legislators amply fund public schools? Probably not. But maybe in 2029...

This week the Washington State legislature convenes in Olympia for its 2026 session. Once more, legislators and the governor will come under public pressure to solve the financial problems plaguing Seattle Public Schools and many, many other districts by adding new money, something that has wide public support.

Once more, state leaders are likely to abandon schools instead. But there is possible hope on the horizon: a millionaires' tax that could generate billions of dollars for public schools...at the end of the decade.

Despite public school funding being the “paramount duty” of state government according to Washington State’s constitution, legislators and governors have for years acted as if public education is a low priority. The result is that students suffer, and families of all backgrounds are increasingly looking outside the public school system for quality education for their students.

Today we’ll take a closer look at the prospects for school funding in the 2026 legislative session and beyond.

In this issue:

- A Constitutional Promise Never Fulfilled

- The Defense Takes the Field

- The Best Defense Is a Good Offense

- An Income Tax, At Last?

- Don't Play by the Usual Rules

A Constitutional Promise Never Fulfilled

According to our state’s constitution, our schools shouldn’t even be in a funding crisis at all. They should instead be swimming in cash. Washington State’s constitution, adopted at statehood in 1889, contains the following language in Article IX, Section 1:

“It is the paramount duty of the state to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders, without distinction or preference on account of race, color, caste, or sex.”

This remarkably progressive vision is important for school funding for two key reasons:

- Public education funding is the number one priority of the state.

- That funding must be “ample” – defined in the dictionary as “generous or more than adequate.”

Unfortunately, it’s easier to write big promises into a late 19th century constitution than it is to deliver them.

State leaders consistently focus their budget priorities on things other than public education. Legislators, the governor, and even the State Supreme Court continue to permit huge shortfalls in public school funding. Today, not a single school district in the state, even in wealthy cities like Seattle or Bellevue, can say they have amply funded public schools.

Instead, the number of districts facing a serious fiscal crisis continues to grow – whether the district is large or small, urban or rural, east or west of the mountains.

Since 1889 there have been several efforts to try and make the state live up to its constitutional paramount duty. Most notably, in 1932, 70% of voters approved a graduated income tax targeting the rich that would have funded the public schools. But in 1935, the State Supreme Court struck that down, claiming that income is property and thus it could only be taxed by a single uniform rate, as the state constitution requires of property taxes. That court was full of right-wing holdovers appointed by a conservative governor in the 1920s. But the impact of that decision has long outlived them.

For the next several decades various legislators and governors tried and failed to convince their colleagues or the public to adopt a state income tax to fund the schools. By the late 20th century, these efforts petered out. Instead, legislators in the 1990s, flush with a temporary surplus due to the dot-com boom, gave out enormous tax cuts.

The bill quickly came due. The early 2000s recession devastated the state budget. State leaders imposed big spending cuts, including on public education. That triggered a lawsuit: the McCleary case, filed by a family in Chimacum (near Port Townsend) in 2007. The McCleary family argued that the state was violating the constitution by making districts reliant on local levies to fund public education.

We won’t go into full details on that case here – you can read a good summary of it and the ways the legislature’s solution failed over at Washington’s Paramount Duty.

But here’s the very short version of the McCleary case: the state Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that the legislature needed to spend more money on public education. Legislators refused and in 2014 were held in contempt of court.

In 2017 the legislature finally complied, by adopting the largest property tax increase in state history to provide the bare minimum of funding to satisfy the court. But their solution actually left a lot of districts (including Seattle) worse off. One reason: the state’s McCleary solution included a “levy cap,” a limit on local districts’ ability to raise their own funds from property taxes, even if the state continued to provide inadequate funding.

The state Supreme Court ruled in 2018 that all of this was good enough and ended the case, despite a flurry of briefs pointing out the legislature failed to solve the problem and had actually set up new deficits going forward.

Since then, the legislature has been unwilling to revisit the topic of K-12 funding, aside from small tweaks here and there, even as the funding crisis grows worse across the state. Most legislators, even progressive ones, consider public education to be a low priority – even though the state constitution literally says it is their paramount one.

In 2024, House Democratic leaders told one candidate for legislator, a City Councilmember from exurban King County, that her priorities did not align with those of the caucus because she made public school funding a cornerstone of her campaign. Democratic leaders backed a rival candidate instead, who won the election.

The Defense Takes the Field

That brings us to the 2026 legislative session, in which many of the established players in school funding believe their best hope is to play defense, protecting public education from further cuts and maybe undoing some recent damage done in the 2025 session.

The big picture is that thanks to Donald Trump’s reckless economic policies, particularly his tariffs and his budget cuts, Washington State faces a budget deficit of about $2 billion. Governor Bob Ferguson refuses to raise taxes, even on the rich, to close that deficit.

Instead, Ferguson has proposed budget cuts across the board. While he proposed no cuts to “basic education” – a narrow definition of funding the public schools – he did propose many other cuts. Marie Sullivan, the lobbyist for the Washington State PTA, writes a good weekly summary of education bills during the legislative session and this week included the following overview of Ferguson’s K-12 budget cuts:

- $25.1 million by not increasing levy equalization/Local Effort Assistance from $150 to $250 in 2027

- $21.1 million from bus depreciation schedule changes to 15-year cycle

- $19.5 million by cutting Transition to Kindergarten slots by 25%

- $14 million by reducing Running Start FTE from 1.4 FTE to 1.2 FTE (which means students will take fewer credits)

- Allows OSPI to use 1.9 percent of the Materials, Supplies and Operating Costs (MSOC) for grades 9-12 to purchase licenses for the new universal online High School and Beyond Plan.

Final budget proposals from the House and Senate won’t come out until late February, after the state gets an updated revenue forecast. Legislators are free to ignore Ferguson’s proposals, of course, but he also has to be willing to sign their budget into law. That means legislators could reject these K-12 cuts entirely, accept some or all, or propose other cuts of their own.

Legislators are also coming under pressure to fix some of their 2025 mistakes. Legislators expanded the sales tax to cover various services – and neglected to exempt public school districts from that tax. School districts are hoping legislators correct that absurd situation.

The Best Defense Is a Good Offense

That defensive crouch is the conventional wisdom in Olympia. But sticking to that is what caused a public school budget crisis in the first place. The only way out is to refuse to stay on defense, and instead, go on offense: push leaders to raise taxes on the rich to fund public schools.

After all, that’s what the public very clearly wants.

Polling has shown about two-thirds of voters want to increase spending on public education, and want to tax the rich to do it. Actual election results bear this out. In 2024, 64% voters upheld the state capital gains tax against a repeal effort funded by the far right. In 2025, voters elected pro-tax progressive Democrats in every single legislative special election, over their anti-tax competition (sometimes a Republican, sometimes a moderate Democrat).

Last year, Senate Democrats proposed to deliver it. Led by Senator Noel Frame of Seattle’s 36th District, they proposed a wealth tax they called a “financial intangibles tax” that would generate approximately $4 billion per year starting in fiscal year 2027 for public schools.

That proposal remains active, though Governor Ferguson opposed it last spring. Senate Democrats haven’t yet shown any public desire to revive their wealth tax proposal for the 2026 session.

Over in the House, some progressives want to raise taxes right now to avoid cuts. Representative Shaun Scott, of Seattle’s 43rd District, proposed the Well Washington Fund – a statewide version of Seattle’s JumpStart payroll tax on large employers.

Unfortunately, Scott’s proposal does not specify that its revenues would go to public education. Starting in the second year of the tax's existence, 51% of its revenues go to a new account that “would be limited to higher education, health care, especially Medicaid, cash assistance programs, and energy and housing programs.” The remaining 49% would go to the general fund, where public education would have to compete with other similarly underfunded services.

However, Well Washington Fund revenues would initially be available to prevent cuts to schools, including those proposed by Governor Ferguson.

Scott is a strong supporter of funding public education, so the structure of the Well Washington Fund likely reflects the larger House Democratic caucus’s unwillingness to prioritize K-12 public education.

An Income Tax, At Last?

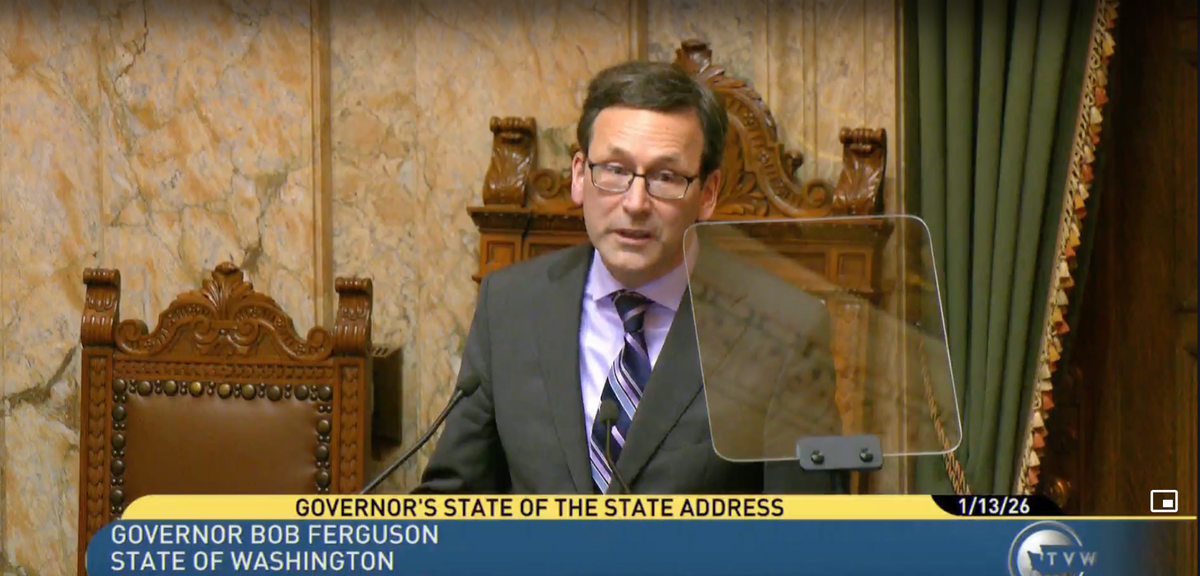

Interestingly, Governor Ferguson has actually proposed taxing the rich to fund public schools – and using an income tax to do it. Just not right now.

Two days before Christmas 2025, Ferguson announced his support for a “millionaires’ tax.” This is an income tax that would create a 9.9% tax on incomes above $1 million per year. That’s on income, not on assets, and the sale of a home would not be subject to the tax.

On the surface this seems like the holy grail is within reach. But it wouldn’t start generating revenue until 2029.

It would be possible to use some sort of other progressive revenue source, like a wealth tax, the state payroll tax envisioned in the Well Washington Fund, or even a higher capital gains tax, to prevent cuts, add new money for schools now, and act as a bridge to when Ferguson’s tax would kick in.

Ferguson did say in his State of the State address today that one use of the revenue from a millionaires’ tax should be to provide more K-12 funding. But that is almost tacked on, mentioned after cutting other taxes. And it won’t actually happen without strong advocacy to overcome legislators’ refusal to prioritize K-12 school funding.

Speaking from a political and electoral perspective, it is difficult to believe voters would support an income tax without knowing that revenue is going to buy them something they really want: like better public schools. And from the perspective of school funding advocates, it doesn’t make sense to push for a long-desired income tax unless it fully solves the school funding problem.

A state income tax on the rich should be modeled on the Seattle Shield Initiative that city voters just adopted in November 2025. Proposed by Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck, it raised the city’s Business and Occupations Tax on the biggest companies, cut it or eliminated it for small businesses, and had nearly $100 million left over to fund public services.

A millionaires’ tax should be structured similarly. It should aim to raise at least $3 billion for public schools, while additionally paying to cut the state sales and property tax to some reasonable degree. Public school advocates should insist on this, or withhold support for a millionaires’ tax entirely.

Don't Play By the Usual Rules

The most important thing for any advocate to know is that if you play by the usual norms and within the conventional wisdom, you will lose. After all, those norms and wisdom created the very crisis you’re mobilizing to solve.

Effective advocacy requires changing the conditions that have caused you to lose into conditions that cause you to win. No advocate can get all of what they want. But persistent, smart advocacy focused on mobilizing the public rather than playing by rules designed to ensure we lose is how to achieve the outcomes we seek.

The hard reality is that nothing will change when it comes to funding public schools until two things happen:

- Parents mobilize across the state to demand legislators and the governor mobilize in large numbers to make elected leaders add billions of dollars to K-12 public schools.

- Voters defeat incumbent Democratic legislators and replace them with Democrats who are determined to add billions of dollars to K-12 public schools.

Nothing else will get the attention of the Democratic caucuses in Olympia. Nothing else will force governors to start taking school funding seriously.

The 2026 session is as good a time to start as any.