Issue 11 -- January 14, 2026 Seattle School Board Special Meeting Recap

The board hears updates about "Life Readiness" and about the state legislative session.

by Julie Letchner

Watch: YouTube Video

Read: Transcript

Agenda & SPS presentation materials: (SPS website)

In this issue:

- Work Session: Progress monitoring of board goal #3 (“Life Readiness”)

- Work Session: 2026 State Legislative Session

Progress Monitoring of Board Goal #3: Life Readiness

Back in December, the board received baseline updates on the first two of the SPS board’s three goals (second-grade literacy and sixth-grade math). On Wednesday, the board received their baseline update on the third and final board goal, relating to “life readiness.”

The purpose behind the “life ready” goal is to assess whether SPS graduates are equipped for life after high school–and, of course, to monitor the proportion of students graduating at all.

Measuring life readiness

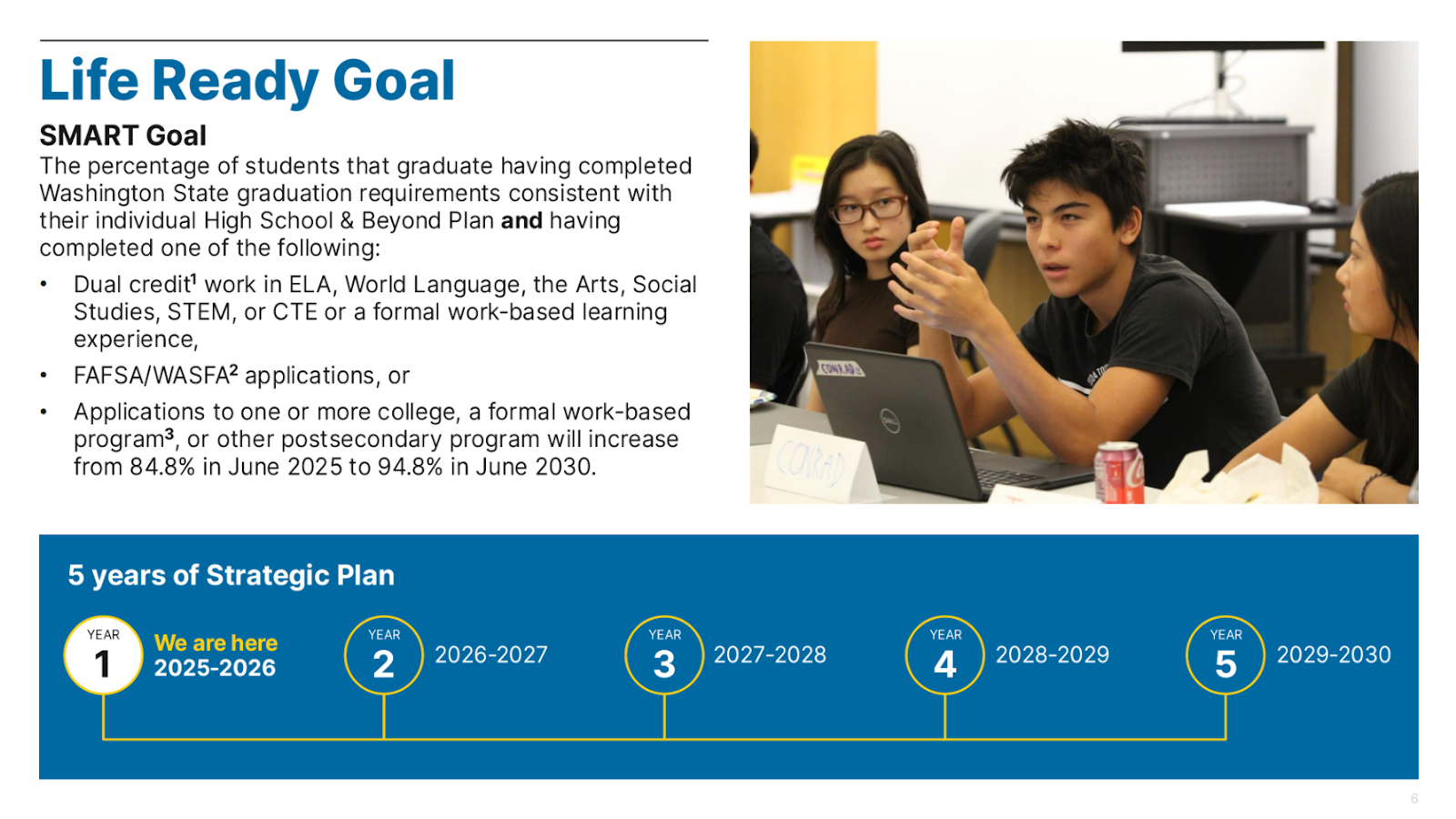

To meet the SPS definition of “life ready,” students must meet two requirements, as shown in the slide below:

- First, they must complete all mandated Washington-state graduation requirements, which include coursework spread across specific subject areas, and some testing requirements.

- Second, they must complete one of three options demonstrating preparedness for a pathway after high school. These are:

- Earning dual credit (e.g., Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate) or completing Career & Technical Education (CTE) training or a work-based learning experience, or

- Completion of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or the Washington Application for State Financial Aid (WASFA) financial aid application, or

- Application to a college or work-based or other post-secondary program

SPS slide detailing the “life ready” board goal. 84.8% of students meet the two-part goal today; the district aims to raise this to 94.8% of students by June 2030.

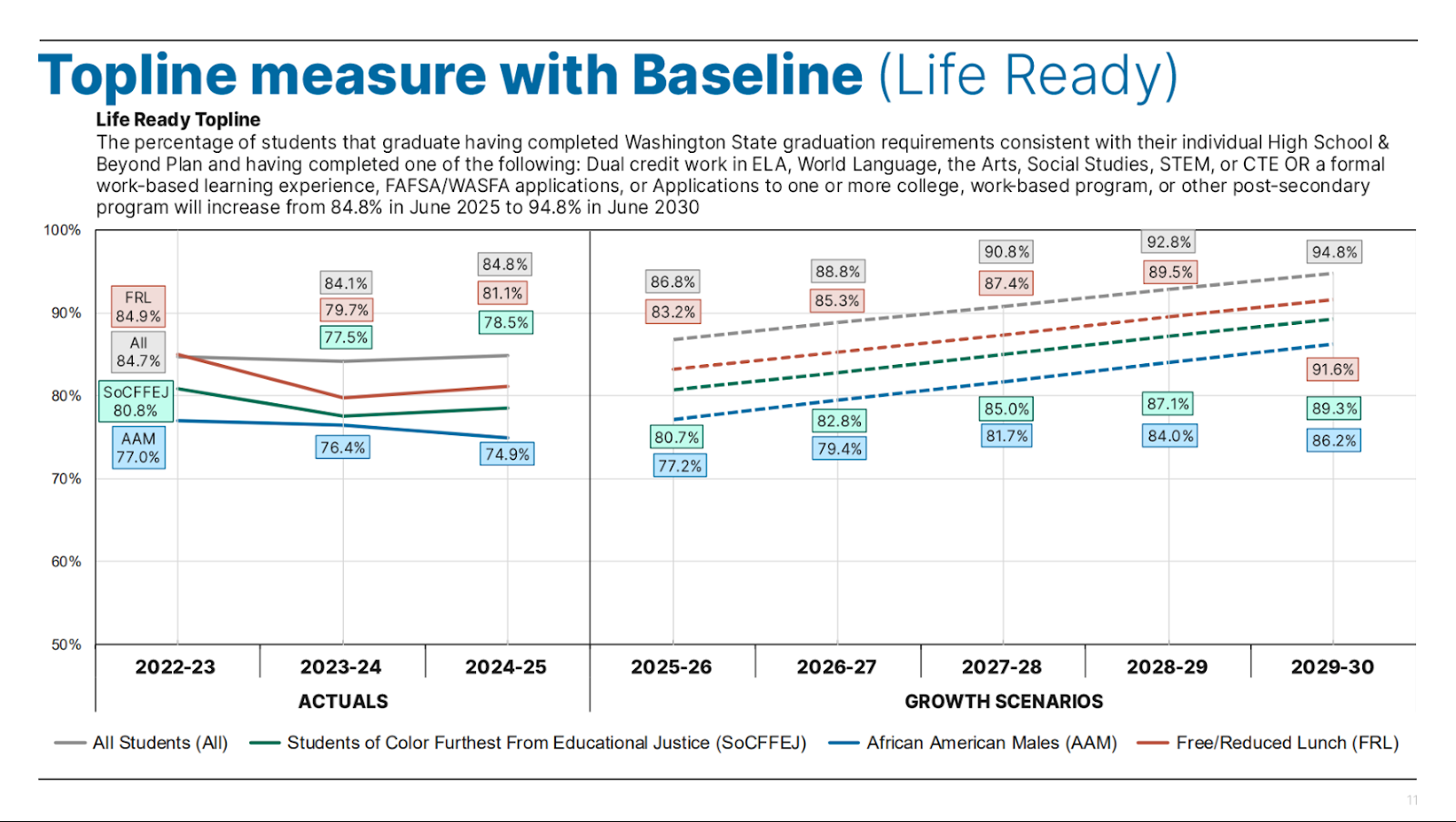

As of spring 2025, 84.8% of SPS students meet this criteria. The graduation rate for Washington state overall is 82.4%, putting SPS slightly above average–not bad, especially considering that the SPS metric requires additional actions above and beyond the state requirements.

Following the pattern of the other board goals, the achievement rate for the life readiness goal is lower among subpopulations facing opportunity gaps: 81.1% of students receiving free and reduced lunch were “life ready”; 78.5% of students of color furthest from educational justice* hit the goal; and 74.9% of African American males met the criteria.

SPS slide showing achievement levels of the “Life Ready” board goal, historically (left) and projected (right).

It is unclear from the district presentation how many “life ready” students are actually meeting graduation requirements, versus graduating with requirement waivers. COVID-era state policies allowing students to waive core course requirements and testing requirements appear to still be in effect. PE and community service hours can also be waived.

Measuring the path to life readiness

In addition to the topline “life ready” goal, the district is also tracking a set of interim measures intended to track whether a cohort is likely to be “life ready” by senior year. These interim measures include:

- 8th grade HSBP (52.5% of 8th graders met this goal in 2025)

Completion of the grade-appropriate components of the High School & Beyond (HSBP) plan. The middle school HSBP lessons include high school course planning and basic financial literacy.

- 10th grade coursework (68.5% of 10th graders met this goal in 2025)

Completion of at least 12 credits (2 each in ELA, math, and science, with a minimum of 1.5 in social studies). There is also a Washington state history component to this interim measure, but most students complete this requirement in middle school.

- 11th grade HSBP (4.6% of 11th graders met this goal in 2025)

Completion of the grade-appropriate components of the HSBP plan, which include course planning, career path awareness, and résumé preparation.

- 11th grade dual credit / CTE (91.0% of 11th graders met this goal in 2025)

Completion of dual credit (in English Language Arts, World Language; Arts; Social Studies; or Science, Tech, Engineering, & Math), or career & technical training (CTE) or a formal work-based learning experience

There are two eye poppers here:

First, 4.6% is an abysmal achievement rate for the 11th grade HSBP goal. Associate Superintendent Dr. Rocky Torres-Morales was frank that completion of the HBSP is not a priority of staff today. The ensuing discussion didn’t point clearly, though, to whether the district plans to prioritize HSBP completion, or scrap this portion of the interim measure.

Second, only 68.5% of 10th graders have earned 12 credits (12 credits by the end of 10th grade means that a student is on pace to earn the 24 credits required to meet the “life ready” goal). If these students don’t catch up, today’s 84.8% goal achievement rate is set to drop 16 points in two years! The only credit recovery program I’m aware of is summer school. Summer school enrollment and completion rates would be important context to include in this interim metric if the district wants to track where kids fall out of the life-readiness pipeline.

Are today’s SPS students really “life ready”?

An achievement rate of 84.8% on the “life ready” goal would seem to indicate that SPS students are largely life-ready. However, much of the board discussion on this topic rightly focused on the fact that the “life ready” metrics don’t include measures of actual skills or competencies. A diploma is not the same as a skill set!

Nearly every director expressed some degree of concern that the top-level “life ready” goal is not properly reflecting student readiness. Directors Vivian Song, Liza Rankin, Gina Topp, and Evan Briggs all pointed out, with varying levels of directness, that graduation rates do not reflect what graduating students know and can do. This criticism is correctly placed, and hopefully it will lead to metrics that better reflect student achievement. It does make one wonder, however: wasn’t it the board who wrote and adopted these goals just last year?

Several directors also expressed concern that today’s SPS graduates are not life ready, regardless of what the rosy metrics imply. Director Song expressed concern over Seattle Promise feedback that SPS students show up unprepared for college and require remedial coursework. Director Briggs added that this problem has been reported even among students who graduate at or near the top of their class.

Director Rankin noted that it’s easy for SPS students to game the system, earning passing ‘D’ grades with little to no understanding of course material. She specifically referenced a Covid-era policy still in place today, that awards 50% credit for any missing work, instead of 0%.

Student Director Sabi Yoon and elected Director Kathleen Smith both noted that completion of the FAFSA form is largely a box-checking exercise, and not an activity that indicates life readiness. Dr. Torres-Morales said that the FAFSA option was likely to be dropped from this goal moving forward, though this decision was based on the difficulty of obtaining FAFSA data and not related to the suitability of FAFSA applications as a measure of life readiness.

The most specific request for change to the life readiness metric came from Director Song, who suggested incorporating measures of actual ability into the metrics. She specifically proposed that existing standardized test metrics might provide meaningful benchmarks. Indeed, the Smarter Balanced Assessment (SBA) is already administered state-wide in 10th grade, measuring English language as well as mathematical skills. The board’s elementary-school literacy and middle-school math goals already use the SBA as a metric, making 10th-grade SBA scores a natural interim metric to investigate.

What’s next for the life readiness goal?

The district’s slides related to what’s been tried before and what is planned moving forward were extremely vague. This makes some sense, given that we are at the beginning of the 5-year strategic plan cycle, and a new superintendent is about to come aboard in a few weeks. That said, the strategies were so unspecific that they left little for the board to comment on, beyond Director Rankin’s affirmation that, “These feel like the right strategies.”

Notably, Dr. Torres-Morales said at the beginning of the meeting that 10% growth over five years is extremely ambitious for any student outcome goal, and that he’d like to revisit that target once incoming superintendent Ben Shuldiner comes online. He elaborated minimally, stating that increasing SPS graduation rates by 10% risks pushing some students—those on “alternate standards”--into unsatisfactory positions. The board’s other two goals—second-grade literacy and sixth-grade math—also aim for 10% growth over five years, and Torres-Morales did not question the realism of those goals when he participated in their baselining discussions with the board in December.

Given the level of feedback in this discussion, it seems likely that we’ll see this goal back on the board’s agenda at some point after incoming Superintendent Ben Shuldiner starts to dig in.

Legislative Update

Cliff Traisman, SPS’s longtime contract lobbyist, and SPS’s Director of Board Relations Julia Warth joined the board for a discussion of the legislative session that began Monday. They reviewed the board’s legislative priorities and discussed the board members’ responsibilities and limitations as advocates.

SPS board-adopted legislative agenda

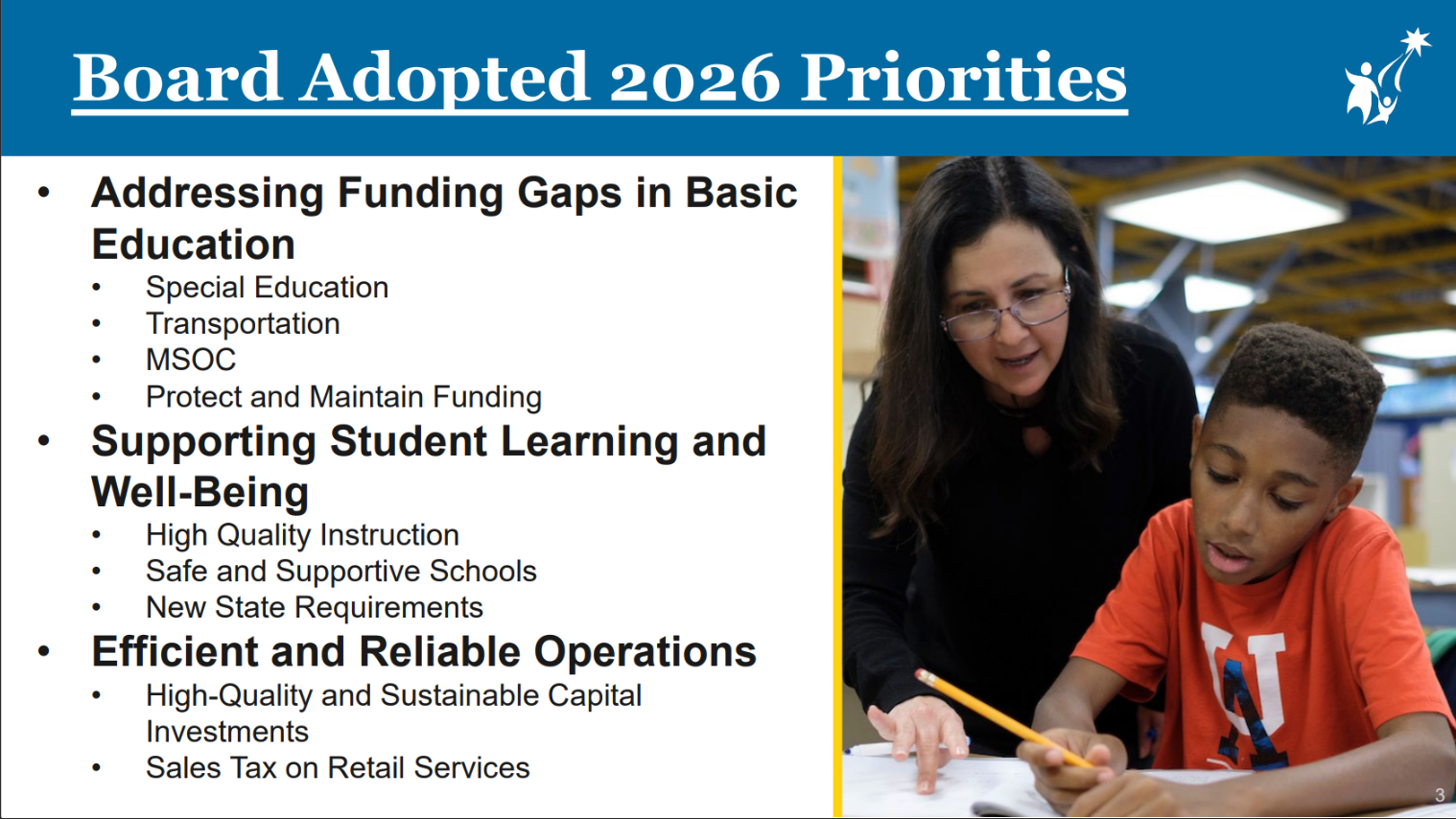

Back in a November meeting, the board unanimously adopted their 2026 legislative agenda. Traisman and Warth reviewed the agenda’s key priorities for the board.

SPS slide showing the 2026 board-adoped legislative priorities.

The discussion focused mostly on funding—no surprise there, given the very public budget shortfall discussion of the past few years. Traisman was blunt: “We can’t afford any losses in K-12 education.” While this is undoubtedly true, it’s also tragic: Traisman and other Olympia insiders believe that all we can expect from the legislature in 2026 is to simply protect against further cuts, rather than an ample funding of K-12 education.

Additional revenue is the only long-term solution for K-12, and two points of hope were highlighted in the board discussion:

First, Traisman is part of a group working to develop a new funding model for Washington State K-12. Washington’s Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal announced in a press conference last week that his office will be announcing the new model as early as next year, and that the model would include new revenue. The current funding model is fraught, doesn’t include enough money to adequately fund education, and doesn’t meet student needs.

Second, Governor Ferguson in December asked the legislature to develop a "millionaire's tax” this session. Part of the proceeds are meant to benefit K-12 education. If that bill materializes and is passed, revenue would flow to schools in 2029 at the earliest.

Board members as advocates: rules & responsibilities

Warth reviewed a set of dos and don'ts for board members when advocating on policy at the state level. These guidelines are rooted in state law and board policy. Based on state law, board members—and lobbyist Traisman—are only allowed to advocate to the legislature on behalf of SPS on issues covered by the board-adopted priorities. This is why the specific language of the board’s legislative agenda matters.

There is some wiggle room. For example: Director Briggs asked whether she was allowed to advocate in favor of a bill that would restrict ICE activity in schools. ICE is not mentioned in the board’s adopted language, but Warth said that they would probably be able to fit such advocacy under the “safe and supportive school environment” clause.

One notable restriction on the board is that members are not allowed to solicit advocacy from the public. Washington State law strictly limits the lobbying that elected officials can do. The law includes provisions preventing elected officials, such as school board directors, from encouraging the public to advocate to the legislature on a certain issue (often known as “indirect” or “grassroots” lobbying).

Near the meeting’s end, board president Topp emphasized during her remarks that all board members have a responsibility to advocate for the shared agenda during the legislative session. Warth and Traisman offered support in connecting the board with legislators and opportunities to testify.

*Students of Color Furthest from Educational Justice (SoCFFEJ) is an SPS-defined designation that includes students who are: Black/African, Native American, Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, Southeast Asian, Middle Eastern/North African, or multiracial students from any of these groups.